The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) was a key element of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Program. The legislation aimed to stimulate the U.S. economy by fixing wages and prices. While it was ultimately ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, several of its labor provisions formed the basis of subsequent regulations.

President Roosevelt signed NIRA into law on June 16, 1933, during the height of the Great Depression. It was intended to “encourage national industrial recovery, to foster fair competition, and to provide for the construction of certain useful public works, and for other purposes.”

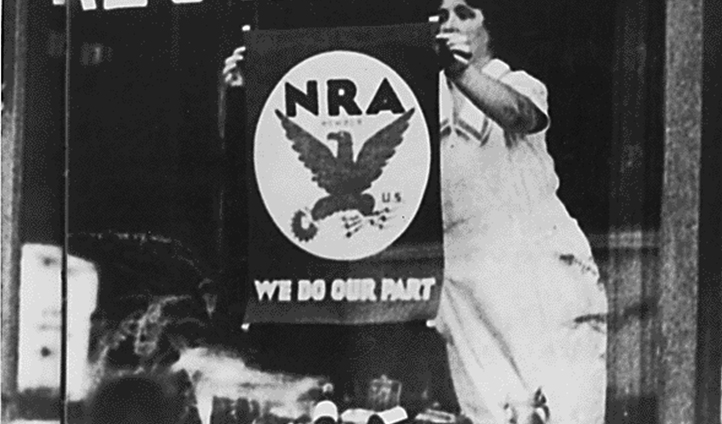

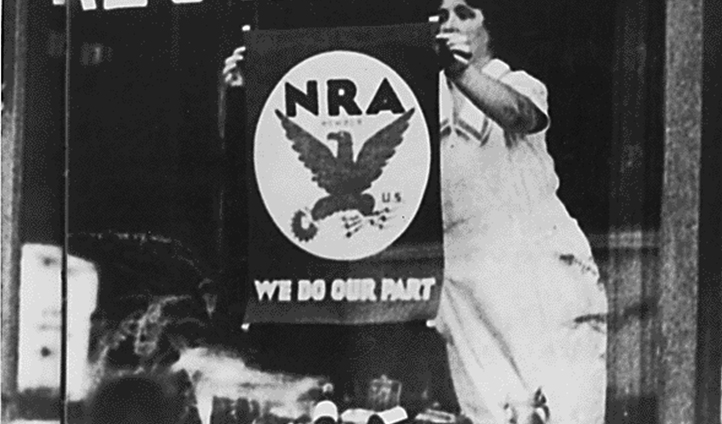

NIRA included two different initiatives. Title I of the act implemented codes of fair competition for several key industries, while Title II established a public works program, which became known as the “Public Works Administration” (PWA). The statute created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to oversee the drafting of the industry codes, and President Roosevelt appointed Hugh S. Johnson as administrator of the NRA.

Like many New Deal programs, NIRA represented a bold change. It mandated that companies formulate industry-wide “codes of fair competition” that effectively fixed prices and wages, established production quotas, and imposed restrictions on the entry of other companies into the alliances. NIRA also established industrial self-regulation, subject to presidential approval. It required each industry to create codes of fair competition, as well as codes for the protection of consumers, competitors, and employers. NIRA also suspended antitrust laws with respect to the codes.

In another major change, workers were authorized to organize and bargain collectively. However, they could not be required, as a condition of employment, to join or refrain from joining a labor organization. NIRA also required the standards to be created regarding maximum hours of labor, minimum rates of pay, and working conditions in the industries covered by the codes, and also authorized the President to impose such standards in the absence of a voluntary agreement. Recognizing that it was intended as a temporary measure to bolster the economy, NIRA included a sunset provision nullifying the regulation in two years.

NIRA was widely criticized by corporate America, workers, and Congress, in large part because each group had competing goals. NIRA also created a dearth of new regulations, with the NRA approving 557 basic and 189 supplemental industry codes in two years. NIRA also resulted in the prohibition of nearly 5,000 business practices. Most importantly, the controversial initiative did little to improve the economy.

In 1935, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down NIRA in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States. The Court held that the New deal regulation violated the separation of powers as an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive branch. The justices further held that NIRA exceeded Congress’ power under the Commerce Clause.